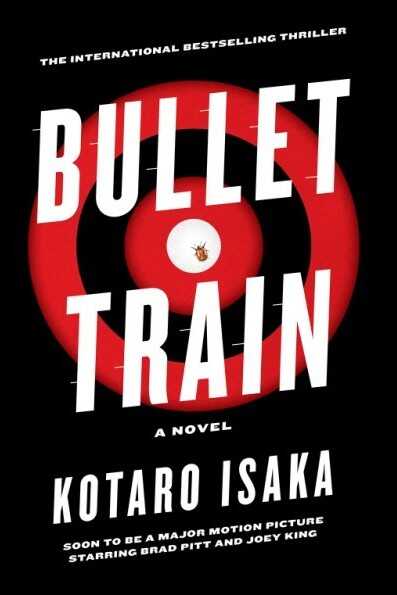

Bullet Train Movie vs Book: Which is Better?

The deluge of adapted material currently being made into awful films and lackluster television series might induce more eye rolls than applause a lot of the time, but sometimes it proves beneficial as it opens a door to even further enjoyment in the form of the glimmering source material. While some adaptations have done good service by their original inspiration, plenty of attempts have generated vitriol and outrage from fans (Rings of Power, anyone?). Traditionally, the phrase “the book was better” tends to ring true. But is that the case with Bullet Train, the 2022 movie vs Isaka Kotaro’s 2010 novel?

In Bullet Train, the book…

Isaka Kotaro’s book is a calculated, controlled, slow burn crime story where the question isn’t “Who killed the dead person?” but “Who is going to survive to the end?” There are sudden moments of intensified action and violence that quickly fizzle back down to psychological anticipation. Each chapter of the novel is told by focusing strictly on the psyche of one specific character or characters (hired assassins Lemon and Tangerine are treated as one entity) at a time. All-seeing readers know everything while the characters struggle to figure out what’s going on, adding momentum and uncertainty to the plot as you rush towards an unfortunately not-so-conclusive end.

A very large percentage of the story is told through mental contemplation and flashbacks occurring inside characters’ heads, particularly Kimura Yuichi (desperate father of a hospital-bound son) and The Prince (psychopath teen who pushed the son and is using Kimura for his own agenda). These two characters and their history, both together and individually, is one of two major pillars that hold up the book (the other being the mysterious death of a crime boss’s son whilst on the Shinkansen) but they are noticeably downplayed in the film for good reason: it’s a long story.

Above anything else, the book is focused almost wholly on the mental and emotional motivations of those involved: it’s a psychological thriller. Everyone has a reason for what they choose to do, and Isaka takes as long as he needs to explain it to you from their point of view. Unfortunately, mental exposition doesn’t really translate well into moving picture, making the overall experience of reading Bullet Train the book very different from watching the film, even if the timeline of events is pretty similar.

What the book does best is give depth and insight into the characters, all of whom are well established and described to the point you can imagine them clearly in your mind. Isaka’s choice of words is very deliberate: you know exactly what he wants you to know about his characters, including limited physical traits. In doing so, the book’s plot and characters are never described in a way that would force them to be exclusively Japanese. Preexisting knowledge of Japanese customs, history, or traditions is unnecessary for the reader to enjoy any aspect of the book, and no extra insight is given if you do have some familiarity.

The novel is about human nature, society’s rules and expectations, and the consequences of our actions. Violence is not drawn out or glorified, unless the character being focused on wants it to be (namely The Prince). There are unexpected and very original twists and turns, making for a totally unpredictable plotline that does genuinely leave you asking yourself who is going to make it out and how. A few events are more over the top than others, but generally the events aren’t as wild as you might expect.

Really, the most wild aspect of the book is how no one else on the Shinkansen seems to notice the violence/murder/blood/etc going on: a key feature of the film, too, that was most certainly included on purpose though I don’t believe that was intentional in the book.

Disappointingly, the book ends in a somewhat vague way with some story points being finished and others not. The reader’s driving question of “Who will survive?” – a question so important that it’s frequently included on the back cover – doesn’t get completely answered, leaving you feeling deflated after wondering for so long. The ending is far from conclusive or climactic, and certainly not explosive like the film. It, like the rest of the book, is about contemplation and asking yourself what you wanted the outcome to be and why.

In Bullet Train, the movie…

When distilled and written down in concise order, the events and plot points of Zak Olkewicz’s screenplay for Bullet Train are mostly spot on when compared to the book, but only up to a specific point.

A single new story line created explicitly for the film – that of the Russian-born yakuza boss known as The White Death – is where the core divergence occurs. Introduced early on and fed to the audience bit by bit, this initially small subplot and outside character eventually takes over the plot in full with all events and motivations circling around them. The White Death is at the root of several scenarios and character backstories, and though he was created by drawing heavy inspiration from another crime boss character featured in the book (Minegishi) the film plays out very differently because of the new additions.

Just because the additions are new doesn’t mean they’re not purposeful or entertaining. The inclusion of a stereotypically Russian bad guy fighting against a bunch of westerners might be pretty cliche, but fleshing a character out to be a tangible criminal mastermind – unlike Minegishi in the book – helps the plot to not only have a more cohesive, simplistic thread running throughout but also reach a conclusive ending.

Focusing the plot and motivations around a central villain also helps fill in the massive gap left when cutting out the extended amounts of mental exposition, specifically from The Prince. It’s a smart move in terms of visual storytelling, allowing for more attention and time to be placed on what’s actively happening instead of why.

The action is exaggerated and possibly an acquired taste, but it does accurately reflect the general insanity and unlikelihood of the events going on in the book. Ladybug (Brad Pitt’s character based on Nanao aka Ladybird) is both very unlucky and lucky all at once, experiencing events past and present that defy all odds. With the film following Ladybug as a central character much more than the novel, the film does whatever it can to highlight the unbelievable reality Ladybug is living in. The result is a radical yet truthful visual retelling of the chaos he has become strangely accustomed to.

So which version is better?

As far as movies go, Bullet Train (released in August 2022 and directed by David Leitch) is not the best made or best acted film out there. It’s just not. It’s a gory, shock-inducing, almost slapstick display of near-constant brutality with dark humour and outrageously unbelievable characters and events woven throughout.

That said, I think it’s a cinematic masterpiece. But don’t take that as my answer to the article’s title question.

The film is intended to be ridiculous, off-the-wall, and borderline psychotic in the same vain as the iconic but abso-bloody-lutely awful Flash Gordon (1980) or, for a more recent example, Kill Bill Vol 1 + 2 (2003 and 2004). These films all garnered intense criticism when compared to the more “respected”, orthodox methods of dramatic storytelling through film. Part of their genius – or ingenious – nature is that those films don’t follow the orthodox methods a lot of the time. They are meant to go against the grain and, most certainly, rub a lot of people the wrong way.

Bullet Train does that. Without question. More than likely, a lot of people it irritates are fans of Isaka Kotaro’s book. But I feel both manifestations of the story can exist equally as individual peers rather than in a superior source material vs inferior film adaptation relationship. They both have wins and losses against one another that ultimately leave them on equal ground.

It is exceedingly rare for both the original source and wildly altered adapted material to shine brightly in such opposing ways, but Bullet Train manages to do it. They are incredibly different creative pieces: in tone, motivations, details, and overall audience experience. Some will enjoy one more than the other, of course. But when you break it down, the film really is an accurate representation of what is already present in the book; the filmmakers have simply chosen to focus on exactly what Isaka didn’t.

The verdict: watch or read?

Both!

As unlikely as it may seem, I highly recommend people experience both as the film and book can be enjoyed independently as well as compliments to one another. So go grab a copy of the book, clear a few hours of time to watch the film, and enjoy all of the crazy things they have to offer in their own crazy ways!